Do the traces look confusing? This guide will hopefully help you make sense of them, and help you further internalize the algorithm itself.

Summary:

Worklist labels summary

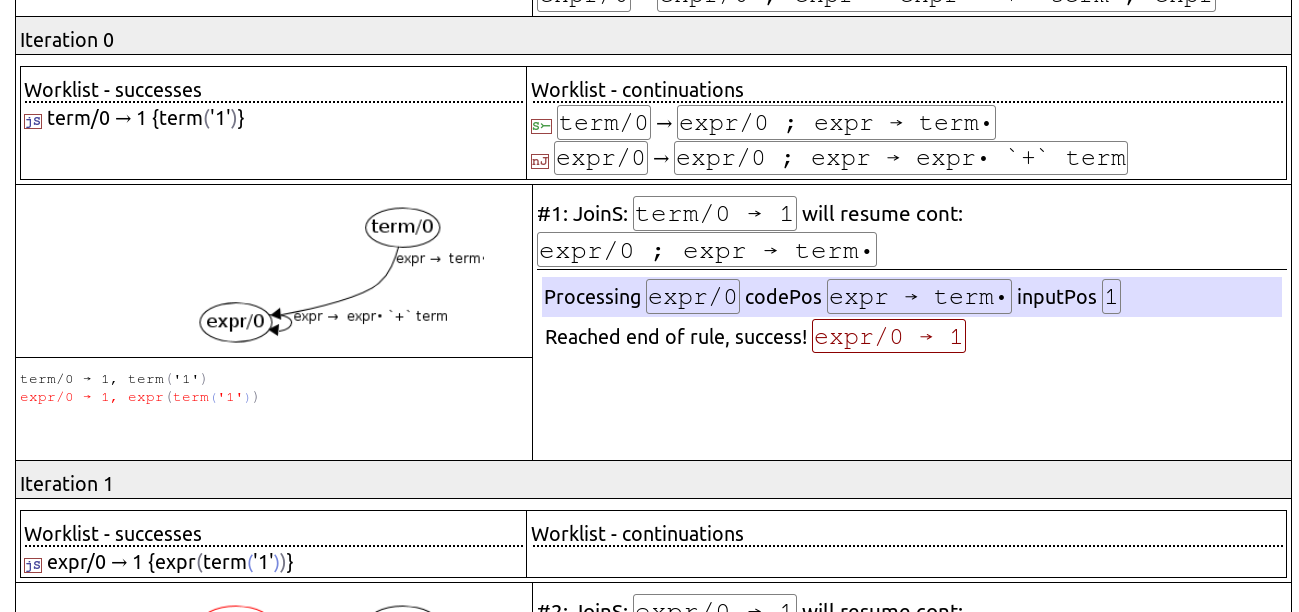

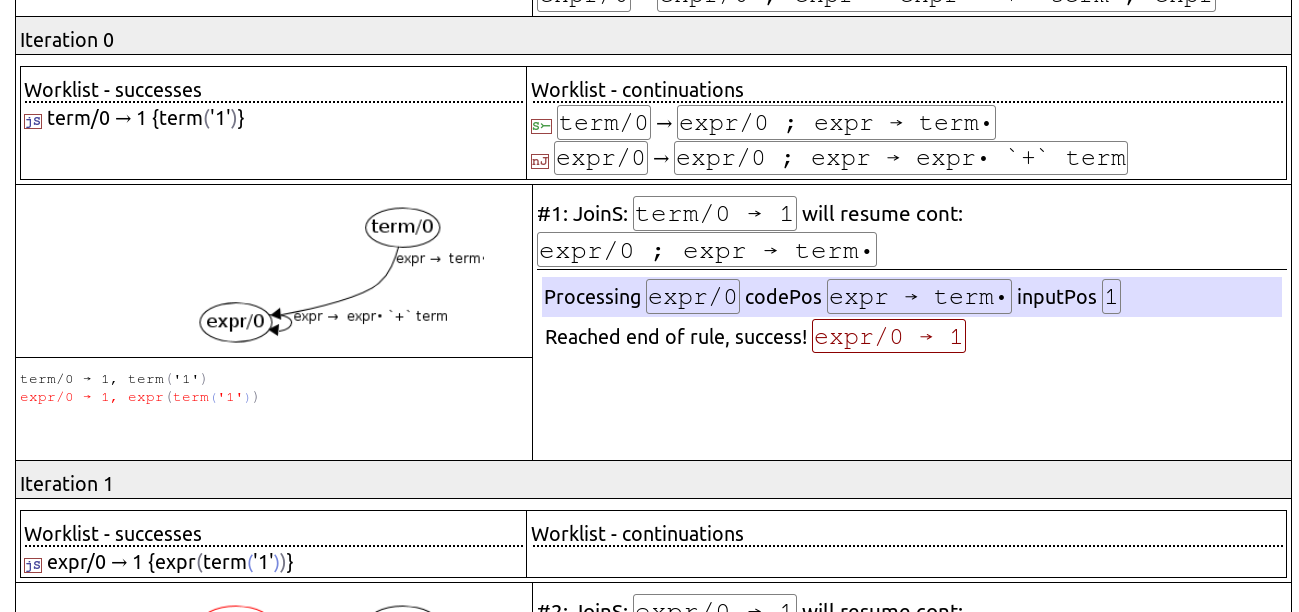

The running of a Takmela program (parsing or Datalog) happens in iterations, each of them composed of a series of steps.

K = {} ; newK = {} ; S = {} ; newS = {} ; awakenings = {}

callRootRule()

while(true)

{

kWorklist = diff(newK, K)

sWorklist = diff(newS, S)

if(kWorklist.size == 0 && sWorklist.size == 0) { break }

newK.clear() ; newS.clear()

K = merge(kWorklist, K)

S = merge(sWorklist, S)

awakenings.clear()

joinNewContinuationsWithPastSuccesses(kWorklist, S)

joinNewSuccessesWithPastContinuations(sWorklist, K)

}

The 'zeroth' iteration happens before the while loop, and the only step therein is calling the root rule. Calling the root rule seeds the rest of the iterations since it can produce new successes (thus adding items to the sWorkList) or produce new calls and their continuations (adding items to kWorkList).

The first section shows the sWorklist and kWorklist, this is important since these worklists determine how the algorithm will go forward in the current iteration (and the algorithm will end when these worklists are empty).

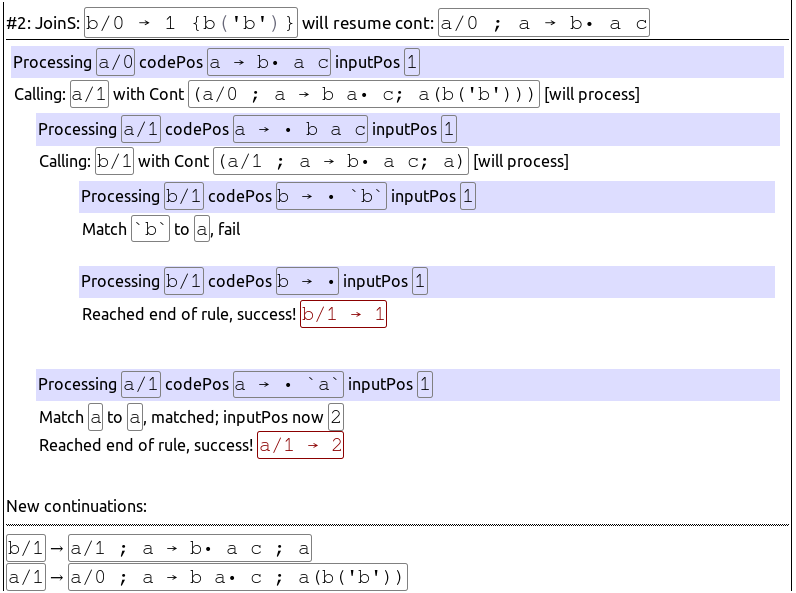

Worklist items (new successes and continuations) move processing forward when they join with other items; a new success can join with a new or existing continuation, and a new continuation can do the same with successes.

The join criteria is the caller/callee relationship: if a new success represents the call a/5, and the K (continuations) table has an entry a/5 → (r/3 ; r → b a • c), then these two can join together to resume processing of the rule r from the specified code point. New continuations can make use of new/existing successes in the same way. The awakenings table is there to prevent the criss-cross problem where a new success and a new continuation join each other twice.

When a success joins a new or existing continuation, we call it a JoinS, and inversly when a new continuation joins a new or existing success, we call it a JoinK

The trace uses labels to show how worklist items join together, as explained below:

| jS | This new success joins a continuation (JoinS). |

| jK | This new continuation joins a success (JoinK). |

| S⤚ | This continuation will be joined by a new success (thus becoming the other participant in JoinS). |

| ⤙K | This success will be joined by a new continuation (becoming the other participant in JoinK); should not be found in the wild unless the algorithm changes, due to awakenings. |

| nJ | This worklist item does not participate in any join during this iteration. |

| F | (Datalog only) This worklist item tried to participate in a join but matching variables failed. |

Inside each step, the algorithm processes a rule's contents. Suppose the algorithm was resuming a continuation such as (r/3 ; r → b a • '+' c d) : here's what would happen

Interestingly, while the call to process is recursive, it doesn't have to be. This isn't the dynamic, unbounded recursion that needs a runtime stack; and a code generator could analyze the grammar and generate a specialized, non-recursive processRuleXyz(..) function for each of the grammar's nonterminals.